Valuations are estimates of how much a company will be worth to a prospective buyer. The most important use for valuations in consulting interviews is in cases dealing with mergers and acquisitions. In order to weigh up our options in such scenarios, we need to be able to compare the potential gains or losses associated with various options - and this means we need to make valuations!

All the best resources in one place!

Our platform is unique in collecting everything you need to ace your interview in one convenient location, for a truly joined up experience. Sign upRisky Business

An important point to note straight off the bat is that valuations can only ever be estimates rather than absolute values. Because valuation fundamentally involves making predictions about the future, there will always be an element of uncertainly or risk. We address these sources of risk in some detail - as well as drilling down into many of the other issues here in more depth - in our full length lesson on valuation in the MCC Academy. Here, though, we will have to confine our briefer discussion to the more immediate nuts and bolts of how valuations are made.

Example: Steel Producer Acquisition

We'll explore the theory around valuation through a reasonably straightforward case study which hinges on your valuing a company.

Let's say your interviewer gives you the following case prompt:

"Our client is a steel producer who wants to expand by acquiring their competitor. The competitor offers to sell their plant for $1M. Should our client accept the deal at this price or not?"

Working through this case will provide a great introduction to valuation!

Identify the problem

As always, your first step in tackling a case should be to correctly identify the problem. This is quite straightforward given this case prompt. In order to work out whether the client should be willing to pay the $1m asking price, we ultimately need to work out what the steel producer is worth to them. That is, we have to establish the value of this second steel plant to our client, to see whether it is worth paying $1m for.

Varieties of value

This might seem simple enough - however, we have not quite narrowed down the specific problem to be addressed yet. There is an extra layer of complexity to consider when identifying the problem in the case dealing with valuation.

This is because there is not one single "value" concept for us to reach for. Instead, the word "value" can refer to several distinct quantities, all of which might be of interest in different contexts. These various varieties of value can be somewhat bamboozling at first, as some are radically distinct from other, whilst some are subsets of one another,. We need to be clear exactly which kind of value we are trying to calculate!

In this case study, what we are interested in is the value which acquiring this second steel producer will offer for our specific client. This quantity is referred to as the Asset Value or the Total Enterprise Value (TEV).

It's all relative...

Note that this value is inherently relative to a particular buyer and will be different for different individuals. In our case, the value of the steel producer will likely be very different for our client, whom is already involved in the industry, to the value which might be derived from a buyer with no existing interests in steel. What we are calculating here is the price which it makes sense for a certain individual to pay for the asset in question.

Build a Problem Driven Structure

Now we know exactly which kind of value we are trying to figure out, it's time to get on and figure out how we are going to get to an answer. This means structuring our approach to the problem.

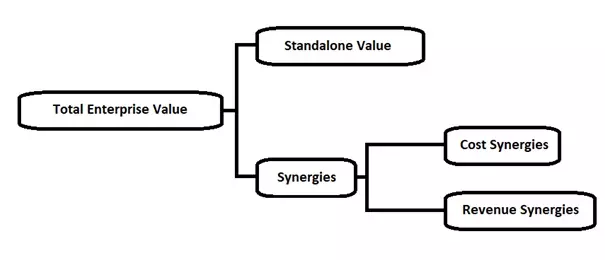

The TEV of the second steel producer can be calculated as the sum of the "standalone" or "market" value of that company plus any "synergies" which emerge when it is combined with our client's operation. Those synergies can be further divided into revenue synergies and cost synergies. Segmenting the problem in this manner yields the following structure:

That was quick enough, but now we need to turn our attention to what the contents of those boxes actually mean...

Standalone Value

We'll deal with synergies shortly, for now, let's focus on how we might calculate the standalone value of an asset - the second steel producer in our example. As per our remarks on the variety of valuations above, there are several ways in which we might go about estimating the standalone value of a company. Three of the most common are:

-

Net Present ValueThis is generally the most robust method of company valuation and is the most commonly used in consulting interviews. This is the method we will use here and we will return to NPV below.

-

MultiplesThis is a method of valuing a company based on the ratio between the company's value and some financial metric such as EBITDA - which stands for "Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation", but which we can approximate as cash flow for the purpose of case interview.

-

Asset Based ValuationIn some cases, the cash flow or similar of a company might misrepresent its value. This might be especially useful in cases concerning businesses like shipping or real estate companies, and especially any companies which might be loss-making, but hold a large volume of valuable assets. In such situations, an asset based valuation calculates the net present value associated with owning individual assets rather than for the company as a whole.

Net Present Value

Let's focus on the Net Present Value, which is more relevant to our example. The NPV represents the value today of the expected future cash flows of the company. This is often referred to as the value of cash flows in "perpetuity".

Join thousands of other candidates cracking cases like pros

At MyConsultingCoach we teach you how to solve cases like a consultant Get startedImagine you have the option to buy some bond which yields you a payment of $20 per year every year. The NPV of this bond is the amount which it would be sensible for you to pay today to receive this guarantee of $20 per year in perpetuity.

In our video lesson on valuation in the MCC Academy, we give a full explanation as to the rationale and mathematics underpinning NPV - which can be very important in tacking more complex case studies involving valuation. However, with limited space here, we'll skip straight to the payoff, and note that the NPV can be calculated via the following equation:

r = Discount Rate

Discount rate

A crucial element of the Net Present Value equation is the discount rate (r). The discount rate effectively accounts for the intuitive fact that a dollar today is not worth the same as the guarantee of a dollar one year from now. In normal circumstances, having the same amount of money immediately will be more valuable than having the same amount at some later point in time. For instance, if you are given your dollar right away, you might deposit it in a savings account and earn interest, so you will have a dollar and a few cents more a year from now.

The discount rate will vary for different scenarios and you might be expected to make a reasonable estimation of its expected level for a case. Generally, the discount rate will be higher where a business venture is more risky. This reflects the higher interest rates which will be required by lenders or investors to entrust their money with a business has a higher risk of never managing to pay them back.

As a rule of thumb, you can think about a spectrum of discount rates ranging from 3% for a very safe business to 20% for a very risky venture.

Synergies

Now, let's turn our gaze to synergies. The possibility of synergies is what will ultimately make our steel producer worth more or less to different buyers, as the new company may interact more or less beneficially with the companies or other assets they already own.

The idea that what one owns already determines how much one is willing to pay for new items if pretty intuitive. Imagine you are selling a collectable item - say a novelty teapot, baseball card or the like. You will obviously get a lot more for it if you find a buyer who needs that item to complete their collection! Higher up the value scale, effects like this are known to cause interesting phenomena in the art market. In particular, there are cases where it makes sense for buyers to pay as much as possible for a painting at auction, as the new market value will increase the prices of the other works in their collection by the same artist by an amount that more than compensates their extra expenditure.

Looking for an all-inclusive, peace of mind program?

Choose our mentoring programs to get access to all our resources, a customised study plan and a dedicated experienced MBB mentor Learn moreReturning to our example, we can divide the possible synergies for our client in acquiring the steel producer into two sides - cost synergies and revenue synergies. Let's look at each in turn.

Cost synergies

Cost synergies are realised when the merging of two companies allows for the reduction of costs. Such synergies might be achieved in a few different ways. For instance:

-

Merging cost centresCombining two companies can allow for the removal of duplicated structures or staff. In our example, the newly merged company might make cuts to staff in supporting roles such as HR, management or R&D.

-

Economies of scaleIncreasing the size of a business often allows for savings to be made by procuring goods or services in larger volumes - and thus for lower prices. For example, steel manufacture will require both raw materials and fuel/energy and a larger operation buying larger volumes of these might be able to negotiate lower prices. Similarly, the larger company might be able to negotiate lower shipping costs on their outgoing products.

Revenue Synergies

Revenue synergies are realised when combining two companies allows them to increase the revenue they generate. A typical way of deriving revenue synergies is via cross-selling, where two merged companies can sell their products to each other's customers.

In our example, cross-selling would be a strong possibility where our client and the acquired producer have previously specialised in different parts of a full spectrum of steel products which the same customers might be interested in buying. For instance, say our client's company has previously only offered large, unshaped ingots of raw steel and the new producer has specialised in smaller slabs or pre-formed items. The newly merged entity could cross-sell to existing customers who need both kinds of product.

Otherwise, revenue synergy could be obtained even if the two had already been selling the same products to the same customers as the newly combined operation might allow the merged company to fulfil larger orders and so access new customers dealing in larger volumes.

Not always a good thing...

Note that synergies will not always be positive. It might be that merging two companies would actually cause problems. For example, it would be highly damaging from a brand perspective for a health food company to acquire a processed food producer, and could cost them a lot in sales. Brand will likely not be a major concern in the steel industry, but will often be crucial in other case.

Lead the analysis and provide a recommendation

With our structure complete, we can proceed to lead the analysis as usual. This will mean asking the interviewer a few considered questions in order to estimate values for the various elements of the structure. Once you have these values, calculating the value of the company is straightforward.

Let's say that, in our example, we valued the steel producer as being worth $1.5m. If there are no other opportunities available with higher values, then we should recommend that our client goes ahead with the acquisition. However, if our client could invest the same $1m in another company or set of assets valued at over $1.5m, then we should advise that they do this instead. Valuation has given us a means to objectively choose between opportunities.

Takeaway

This article is a good primer on valuation, helping you get to grips with the main concepts and walking you through a relatively simple example of a valuation-based case study. However, the problems in your case interview are likely to be somewhat more involved. To get across all aspects of valuation in the detail you will need to land an MBB consulting job, the best resource is the "building blocks" section of the MCC Academy. There, our full length video lesson explores more complex aspects of valuation - including things like a full discussion of risk as it pertains to case studies and of the mathematics around net present value. We do our best, but it simply isn't possible to cram all this material into an article of this size!

For now, though, you should certainly start applying what you have learnt here to practice case studies. Remember to also check out our other building block articles on estimates, profitability, pricing and competitive interaction to learn about more themes that come up again and again in consulting interviews!

Find out more in our case interview course

Ditch outdated guides and misleading frameworks and join the MCC Academy, the first comprehensive case interview course that teaches you how consultants approach case studies.